When Push Comes to Shove: What to do with Children’s Aggression

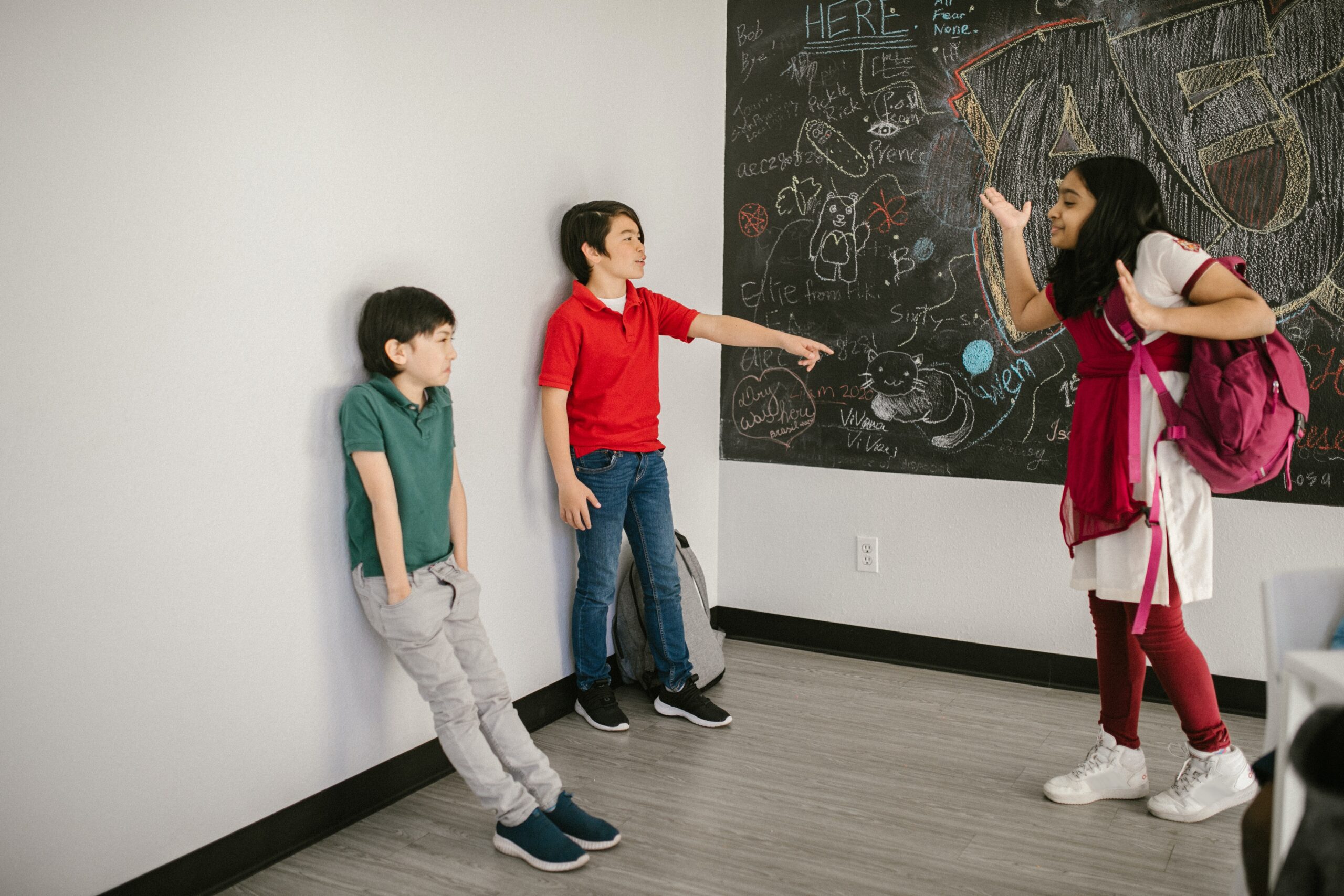

Aggressive behaviour in children can be alarming. Hitting, screaming and yelling, fighting with others, and even eye rolling are emotionally charged actions that can leave parents at a loss for how to respond.

Getting to the root of aggression is key to helping your child navigate their feelings and develop self-control. If we focus only on our child’s aggressive behaviour and lack insight into what drives it then we may view our child as mean-spirited, entitled, spoiled, inconsiderate, or in need of retaliatory “tough love”. We may be provoked to respond with threats, punishments, and even physical force, which exacerbates the problem and does little to help our child mature emotionally.

In short, it is hard to change a child’s behaviour when you don’t grasp what fuels it.

By understanding aggression and the role it plays in human nature, adults are in a better position to help change the behaviour at a root level. The good news is there a lot we can do to support a child in developing self-control over their big emotions.

It’s nothing personal

As a parent, you’ve likely experienced how a child’s emotions can change seemingly without warning—from happy and content to screaming and stomping at some perceived wrong. This lack of tempering and self-control in children isn’t personal but developmental. A very young child may promise they won’t hit again only to turn around and strike someone minutes later. When asked why they didn’t stop hitting they might say, “I forgot.” And as frustrating as that statement can be, in that moment, they are likely being truthful, as a child can only keep one thought or feeling in their head at a time. By the age of seven, kids who are maturing well have developed the cognitive capacity to better manage their emotions.

Too often we take our children’s emotions personally instead of seeing them as a means of communication.

When we shift our perspective on aggression, we are more likely to gain insight into the emotions that are driving the child and focus on helping them develop emotional maturity. Our children’s emotions are the way their brain moves them to solve problems, and they are hard-wired to demand expression.

Frustration cues, aggression answers

Many people assume that aggression is the result of anger. However, there is a more fundamental emotion that fuels aggression: frustration. Frustration is the emotion that moves us to seek change—whether to make something happen or to make something stop happening. When it collides head-on with the realization that there are certain things we just can’t have or are unable to change, frustration is compounded, sometimes giving way to aggressive behaviours. The job of parents is to help little ones navigate their frustration by finding words for it or alternate forms of expression that don’t hurt others.

Rather than just focusing on getting a child to stop the behaviour, the trick to dealing with aggression is to focus on the feeling behind the action.Frustration in the child is where we need to pay attention and recognize what we may have missed, like a child who is tired or hungry. A child’s frustrated actions are a call to us to take the lead and change what isn’t working, rather than just engaging in a head-to-head battle. Sometimes it’s as simple as providing a snack or instigating naptime, but there are also times when we can’t change what isn’t working and need strategies to help them accept the limits and boundaries that come with life.

1. Lead through the storm

Understandably, children aren’t always eager to accept our limits and restrictions; in fact, they are well known for pushing back against them. Part of the challenge in dealing with children’s frustration is not letting our own frustration at their actions make matters worse. When we punish or administer consequences, we effectively fuel their frustration which often leads to an escalation of attacking behaviour. I once overheard a mother punish her child because he didn’t follow her by taking away his screen time. Not only did he still not follow, but he hit her and the escalation of aggression between them grew. Instead of meeting the child where he was and working through his perceived defiance, the mother’s emotions led them into a dangerous spiral. As tough as it is, we need to try and stay out of the aggression whirlpool and plant ourselves firmly in the ground of the relationship.

2. In the key of empathy

In difficult moments, it can feel daunting to be patient in the face of a child’s frustration, let alone aggression. It can be helpful to focus on frustration and to come alongside their emotions, from the unpleasantness of the decision you have made—whether it’s having to follow along in a boring grocery store, or not getting another cookie, not being able to stay up late, or not attending a much-desired event. Granting a child the time and space to grasp and realize that life is full of disappointments and helping them acknowledge that it feels bad is time well spent. If the child is moved to tears, then the frustration is shifted to sadness, and away from hurting others.

3. Preserve your relationship

What happens when the opportunity to calmly commiserate or wipe away tears of disappointment has passed? When a child isn’t ready to give up what they want, their frustration can be outright foul. Hostile behaviour, throwing, biting, screaming, head-banging, fits of rage, and verbal insults can result as that venting ramps up into aggression.

One of the most important things we can do when a child is lashing out in frustration is aim to preserve our relationship with them, especially since a lack of connection in such times can make aggression worse. This means leading through the impasse by being patient, yet firm, and possibly changing the circumstances around the child, such as removing items that can be thrown, and taking other children out of harm’s way. It is especially helpful to stop what we are doing and give a child our full attention without giving in to our own frustration.

Gently reminding a child that frustration needs to be expressed through words that aren’t hurtful is an important strategy. Similarly, preserve their dignity by avoiding statements like, “You are so mean!” or “Why do you hurt people?” These succeed only in shaming the child and suggests there is something wrong with them for having the emotion of frustration.

By coming alongside the child and acknowledging that they are having a hard time, you help reduce the aggression and keep the relationship healthy.

Handling an aggressive situation when your own reserves are drained can be hard to do, not just for you, but also for your child. In a worst-case-scenario where patience is stretched to its thinnest, aim for doing no harm to the relationship before you attempt to quell the storm. To keep everyone’s dignity intact, it’s okay to wait until emotions have discharged before talking to your child about what was driving them and what your expectations are.

We all know (or have been parented by) parents who dismiss, suppress, or debase their children’s feelings. While in the short run it might produce a docile child, muzzling the emotions can lead to problems with emotional and behavioural combustion down the road. Rather than using logic to convince feelings to go away or denying the realness and legitimacy of emotions, children need the opportunity to express, recognize, and mature into their feelings. The real answer to aggression is supporting a child’s healthy emotional development and to grow within them the ability to control, reflect on, and find civil ways to deal with their big emotions. •

Dr. Deborah MacNamara is the Director of Kid’s Best Bet counselling center, she is on Faculty at the Neufeld Institute, the author of Rest, Play, Grow: Making Sense of Preschoolers (or anyone who acts like one), which has been translated into 9 languages, and a children’s picture book The Sorry Plane.

This article first appeared in EcoParent Magazine Winter 2019, www.ecoparent.ca