The Trouble with Time-outs

The Trouble with Time-Outs

Time outs have become a popular disciplinary practice, aimed at replacing spanking and broadly supported by health and parenting professionals. Like a magic wand, they seek to immediately change a child’s behaviour but rarely is the question asked, “Why do they work and at what cost to the child? From the naughty chair to sending a child to their room, time-outs typically involve excluding or isolating a child from others and/or activities. Time-outs are hailed as a ‘success’ when a child returns from one willing to listen and behave but what is the long-term impact on a child’s development and their relationship to adults? Based on the last seventy years of research in developmental science, it is clear the reason time-outs ‘work’ is the same reason we shouldn’t use them in the first place.

The problem with disciplinary advice given to parents today is it is often disconnected from developmental science and fragmented, not taking into account how a child grows and matures. The benchmark for measuring disciplinary success is whether problematic behaviour has stopped with the belief that a child has learned a lesson. Changing a child’s behaviour in the moment does not equal maturity – one is a short-term solution – the other is a long-term proposition. We have become preoccupied with what to do in the moment and have lost sight of the bigger question. We need to consider how our approach to discipline helps to foster or erode the relational conditions our children require to grow as socially and emotionally responsible beings. Discipline doesn’t make our kids more mature, it is what we do to compensate for the fact that they are not. Discipline is how we provide order to the chaos that immaturity brings. The question is not whether we remove our children from others and activities that are clearly not working, (e.g., having a tantrum in a restaurant), but how we can do this while preserving our relationship with a child as well as their emotions.

Why do Time-out’s ‘Work’ to Extinguish Behaviour?

Time-outs work because they trade on a child’s greatest need – connection. The emotional system in a child is geared towards preserving proximity with their closest attachments and trumps physical hunger. Attachment is defined as the intense pursuit for contact and closeness with an adult, feeling significant, that they are cared for, known and understood. As Urie Brofenbenner the founder of the Head Start Program, said, “Every child needs at least one adult who is irrationally crazy about him or her.”1 The womb of personhood is a relational one and it is our connection to our children that unlocks their potential to mature.

Parent and child relationships are critical when it comes to being able to care for them as it fosters dependence on us, should create a sense of safety and protection, enable us to impart our values, and point our children towards civilized relating when required. As a result, a child’s emotional system is designed and governed by impulses and instincts to preserve connection with their caretakers. It is the hunger for connection that time-out’s prey and rely on, exploiting a child’s greatest need.

What a time-out can represent to a child is that the invitation for relationship is withdrawn unless conduct and behaviour changes. This is the essence and definition of a conditional invitation for connection. If a child deems the relationship with the adult as being worth preserving, their alarm system will press down on other emotions in order to tuck them back into relationship with this adult. In other words, if the emotions you are experiencing and expressing lead to a disconnection with your adults, the brain will strategically move to depress these and move a child into restoring contact and closeness with a parent. The reason a child returns from a time-out willing to behave, to listen, to be ‘good as gold’ is because their emotional system has been hijacked by alarm and they are driven to preserve connection by being ‘good.’

Time-outs are the ultimate sacrifice play when it comes to a child’s emotional world. Developmental science is unequivocal in its findings that both relationship and emotion are the two most important factors in healthy development. Time-outs in the way they are used to separate a child from others and activities can injure both the relationship and emotions in a child. The child’s hunger for attachment as well as emotional expression collide upon each other but the need for relationship takes the lead. It is not uncommon to see alarm problems or frustration pop up in other places in a child who is stirred up this way. It can be released on a sibling, a pet, another child or objects, whenever an opportunity presents itself. It can also provoke defensive instincts to back out of attachment and to numb vulnerable feelings.

Time out’s work because we use a child’s greatest need against them, the disconnection pushes their noses into their hunger for connection and boomerangs them back into behaving. There are many forms of time-out’s given to kids today from giving someone the cold shoulder, withdrawal of love, tough love, counting to three, and ignoring. Each of these convey a conditional invitation to be in our presence according to behaviour and conduct.

Why Time-Out’s Don’t Work for Every Child

Time-outs don’t extinguish problematic behaviour in all children. They are often too provocative for sensitive kids and can evoke a strong alarm response. This may lead to the child defensively detaching from their adults altogether, for example, running away or hiding.

Time-outs also won’t ‘work’ well with kids who don’t have a strong enough attachment with an adult who is using them. If there is little desire to be connected or good for that adult then the separation caused through a time out will not activate a child’s pursuit for connection. There are many reasons for a lack of relationship but it be a sign that a child has defensively detached from an adult if there had been a prior connection.

How to Move Away From Using Time-outs

The question I am often asked is “what do I do instead of time outs,” and “what do I do if I have been using them?” There are many online resources I have added at the end of this article meant to help with this question. One of the easiest ways to discipline is to supervise kids and provide direction. If a child doesn’t listen or want to be good for an adult, it may be less of a discipline issue and more of a relational one. Cultivating a stronger relationship with a child and collecting them before directing them should help in many scenarios.

If time-outs have been used then a parent or adult can start going with a child to quiet space or a different place or choosing to remain exactly where they are in the face of incidents. Trying to focus on the relationship and what is stirring a child up is key, with potentially moving the discussion about an incident to when strong emotions have subsided.

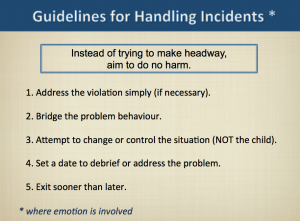

The following 5 Guidelines for Handling Incidents created by Dr. Gordon Neufeld, and used with his permission, are from the Neufeld Institute’s Making Sense of Discipline Online Course. They are particularly helpful in situations where emotions are involved, rather than at times when simply instructions will suffice in redirecting a child. The aim is to not try and make headway in the moment but in aiming to do no harm to the relationship until things can be addressed later.

In addressing the violation we are cueing the child to what is appropriate and not appropriate when it comes to behaviour. For example, we might say, hands aren’t for hitting, toys aren’t for throwing, and it isn’t okay to talk to an adult that way. As Neufeld states, we can drop the “infraction flag” and point out what isn’t working without identifying the child with their behaviour. We can bridge the problem behaviour by conveying we still desire contact and closeness with them despite their actions. This doesn’t ‘reward’ a child for problem behaviour, it merely ensures that you can use your connection with a child later on to influence them in acting a different way or in helping them understand their emotions, name them, and respond in a more civilized manner.

When a child is out of control we often try to control the child instead of the circumstances. If a child is too frustrated in playing with others we can change the circumstances and provide some reprieve. If they have jumps in them or are overly active, instead of getting them to sit down and relax, we can help them move by playing outside. When a child is most stirred up emotionally, our attempts to control them and their emotions often backfire. We may need to compensate and bide our time, changing the circumstances around a child until we, and they, are in a better place to make headway.

We can also let the child know we will debrief or talk about an incident later. In the heat of the moment we are often not able to proceed in a way that can protect and hold onto our relationship with our kids. They are often too stirred up to hear what we have to say. Simply letting the child know when something hasn’t worked out and that you will follow-up with them later, helps them understand that something needs to change and you are there to help them with this.

If a situation is emotionally charged and adverse, exiting from the incident sooner than later can be beneficial. Emotions tend to fuel further emotions such as frustration and alarm and when we are stirred up it is best to pause from proceeding. While we take a break from the incident, it is important to convey that the relationship is not broken. While we may need to be firm on behaviour, we can be easy on the relationship.

What the practice of time-outs cost us long term are the strong relationships with our kids that we will need to steer them towards maturity. We need to become more conscious of the risks to their development as well with how time-outs can evoke defenses against emotions and vulnerability. As Gordon Neufeld states, our kids need to rest in our relationship and not work to keep it. We must be the ones to hold onto them and what is clear is that time-outs make our kids work for love. There is a better way.

For more information on discipline that is attachment based and developmentally friendly for young kids, see Chapter Ten in Rest, Play, Grow: Making Sense of Preschoolers (or anyone who acts like one) and/or take the Neufeld Institute course, Making Sense of Discipline with Dr. Gordon Neufeld.

Deborah MacNamara, PhD is on faculty at the Neufeld Institute and in private practice working with parents based on the relational and developmental approach of Gordon Neufeld, PhD. She is the author of Rest, Play, Grow: Making Sense of Preschoolers (or anyone who acts like one). Please see www.macnamara.ca for more information or www.neufeldinstitute.org.

References

- Larry K. Brendtro, “The vision of Urie Bronfenbrenner: Adults who are crazy about kids,” Reclaiming Children and Youth: The Journal of Strength-Based Interventions 15 (2006): 162–66.

Resources

Discipline for the Immature, Chapter Ten in Rest, Play, Grow: Making Sense of Preschoolers (or anyone who acts like one)

By Dr. Deborah MacNamara

https://www.amazon.com/Rest-Play-Grow-Making-Preschoolers/dp/0995051208/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1467908921&sr=8-1&keywords=rest+play+grow

Making Sense of Discipline, Online Course, Neufeld Institute

By Dr. Gordon Neufeld

See a preview of the course here — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mK7qui2BsfY

Course Description

Are Time-outs an effective form of punishment? Video from Kids in the House

Dr. Gordon Neufeld, Founder of Neufeld Institute https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=So7sJW23xM8

Positive Parenting Alternative to Time-outs and Grounding,

By Nicole Schwarz at Imperfect Families

http://imperfectfamilies.com/2016/07/04/9-positive-parenting-alternatives-timeout-grounding/

Pulling Weeds: Shifting from Discipline to Nurturing the Whole Child,

By Rebecca Eanes (author of Positive Parenting: An Essential Guide)

http://www.positive-parents.org/2016/05/pulling-weeds-shifting-from-discipline.html

The Problem with Consequences for Young Children

Dr. Deborah MacNamara

https://macnamara.ca/portfolio/the-problem-with-consequences-for-young-children/

Soliciting Good Intentions: A Discipline Strategy That Preserves Relationships

By Dr. Deborah MacNamara

https://macnamara.ca/portfolio/soliciting-kids-good-intentions-a-discipline-strategy-that-preserves-relationships/

Why Kids Resist and What we Can Do About It

By Dr. Deborah MacNamara

https://macnamara.ca/portfolio/why-kids-resist-and-what-we-can-do-about-it/