Leading Through Sibling Conflict

My younger sister used to poke me when I wouldn’t play with her. My first strategy was to tell her to leave me alone and when that didn’t work, I would ignore her, which also didn’t dissuade her. At some point I would become so frustrated that I would swat at her like a fly to make her go away. She would scream and cry and I would get in trouble, commensurate with the level of her distress and tears. As a child it seemed to me that the person who was bleeding, crying the loudest, or most upset—usually my sister— was uncritically deemed the victim with the perpetrator assumed by default. A swift verdict would follow.

There are few more provocative things for a parent than watching the children you love get hurt or hurt each other.

Our instincts and emotions are there to protect and defend our kids and can kick into high gear when we witness acts of aggression, meanness, and immature behavior as our children attack each other. But our own impatience and annoyance can add more fuel to the fire of frustration that is already burning, and it can be costly to our relationships with them.

There is no greater test to a parent’s maturity than dealing with the immature ways of relating that our kids present. How do we bear witness to acts of aggression while keeping our cool and remaining in the role of the adult? And how do we lead through these difficult situations while protecting our relationship?

Them’s fighting words!

In the heat of the moment, your kids will tell you just about anything to get the heat off of them. We don’t need to follow our kids when it comes to discovering the reasons why they’re fighting but we will need to make sense of what is truly driving the problems between them. When you understand the roots of “misbehaviour,” it can be tackled it in meaningful ways that lead to change.

When kids fight, they are ultimately fueled by frustration, the emotion of change that wants something to stop or to be different. Children under the age of six don’t have sufficient brain development in the prefrontal cortex to temper strong emotions. Frustration can spill out of them unchecked by any braking mechanism in both verbal and physical forms of attack. Children under the age of three often unleash physically whereas older children have learned to use their words to attack. “I hate you and you are not coming to my birthday party” is a popular threat with the school-age set.

There are many factors that contribute to kids fighting with each other. Based on developmental science and my experience in private practice working with families, these are some of the most common.

You can’t always get what you want

It is a sign of good development when a child has their own mind and can voice their needs, preferences, and desires. The challenge arises when they are engaging with other kids who don’t share those desires. Disagreements over how to play with something, what character they are, or the rules of the game can lead to frustration spewing forth. What we often miss is that each child is meant to develop their own will and it’s only because of their immaturity that they struggle to accept a difference of opinion with others, leaving them at an impasse and frustrated because they cannot solve it.

The futility that children will struggle with—that we are all challenged by—is that we can’t always get what we want. Not everyone wants to do it our way, nor shares our ideas and dreams, and one of the hardest lessons to learn is how to accept the things we cannot change. Kids are in the process of learning about the futilities of life and may need help coming to terms with something that is not going to go their way, even when there is a level playing field. For example, in a game they perceive to be losing, they may fight over the rules and try to force their agenda on their sibling. This is where it is important for adults to step in and reinforce the ground rules for interaction and game-playing.

When my eldest was five she loved playing cards but every time she started to lose she would tell her sister, “Well losers are the winners and winners are the losers.” As I kept a watchful ear on their playing I would often intervene and state something to the effect of, “No, that is not how the game is played. I understand you are frustrated with your cards but keep trying. There are some games you win and some you don’t.” There were many times she would just throw her cards into the air in frustration and I would declare her sister the winner. With time, patience, and support for her tears in the face of frustration, she learned to accept the futility of trying to change the rules to suit her.

What helped me remain patient throughout these episodes is knowing that her immature way of relating was not personal but developmental, and that these were the teachable moments that helped me prepare her for a world where there is no shortage of disappointments.

It is also helpful to think ahead of problems and to set up interactions between kids with some guidance. You might say, “When you play together you are both going to have ideas and things you want. If you can’t figure it out then come and get me, or work together to compromise if you can.” Depending on the age of the child, different strategies may be used. Preschoolers will definitely need more direct help, but older children can become more skilled at navigating these differences, particularly if they care about playing together.

Territoriality and possessiveness

We are thoroughly invested in having our children share and get along with each other, and have very little patience for disagreements. I often wonder if we have the same expectations of ourselves? After all, are we all that enthusiastic about handing over our cherished possessions for others to use? Don’t we also feel that instinctive reluctance to surrender things that we love?

We need to step back and consider whether we really don’t want our children to voice disagreement with others when their territory is under threat. What we should want is for them to know when to stand their ground to protect something of meaning as well as to know when to share. The challenge is that the instincts and emotions to protect one’s place are not bad, but they eventually need to be balanced by caring about others so that we can become socially responsible and emotionally generous, and that is where parents come in.

What children reveal is the chasm between primal territorial relating and this communal thinking.

Part of maturity is being able to relate to others in a conscientious way and to share and work together towards a common goal. It is the role of adults in a child’s life to help close this gap by simply creating the conditions for good development that then naturally reach this end. This means providing enough attachment to satisfy their hunger for a relationship and helping them accept the futilities—like “You can’t have it! That’s mine!”—that are part of life.

When children are full of caring and can also consider the needs of others and theirs, they will have the necessary ingredients to share and get along better and temper their territorial instincts. But these developments occur at the earliest between 5 and 7 years with healthy brain integration. Until then, it is our job to simply and regularly communicate the value of sharing, the importance of having your own mind, and the reminder that you can’t always get what you want. Supervise young kids to prevent territorial disasters from unfolding and reaffirm that turn-taking is part of life, and that you are there to help them.

Attachment-seeking behavior

Kids seek connection, and when they are bored or hungry for attachment, they may seek each other out, especially if adults are not available. Just as with adults, the challenge is that sometimes kids don’t want to play with each other, or they just want to be on their own. This attachment- seeking energy is what drove my sister to poke at me, but I had other ideas for my time, like reading my books. When I wouldn’t reciprocate and give her connection, she continued to pester until things eventually erupted. In such situations, an adult needs to step in and provide the desired connection, redirecting away from using a sibling to fulfill their child’s attachment needs.

Displaced frustration

One of things we often miss when our kids are frustrated with each other is that their emotions may have their roots in something other than the currently raging conflict. A child can be stirred up by something that didn’t go their way in an unrelated situation, and later take it out on their sibling. A brother or sister can be a lightning rod that unleashes emotional energy such as frustration.

One of the biggest sources of displaced frustration for a child is from relationships that do not work for them.

It is often emotionally costly for a child in trouble to fight back against a displeased parent when their relationship may be on the line or they are overpowered, or when separation-based discipline is used (e.g., consequences and timeouts, which can also hurt the relationship). If a parent is upset with a child, then that same child can often turn around and unleash their frustration onto their sibling. The less a child feels emotionally safe in communicating their frustration to an adult, the more likely this frustration will be displaced onto the shoulders of other children.

The Heat is On

Making sense of the reasons why kids fight is helpful, but what do we do in the heat of the moment? The following strategies can help you consider how you might intervene in a way that preserves the dignity of everyone involved, as well as your relationship with each child.

Don’t play judge and jury

Intervening in a way that doesn’t convict or lay blame on one side is important. Kids often will say, “You like them better,” communicating a sense of betrayal at the relational level. The bottom line is we don’t often know who is right or wrong but what we do know is they are having trouble, what they are doing is not okay, and that they need our help. While we can convey that the whole situation is not okay, we can also let them know we see they are both hurt, and that we believe they can do better. The idea is to get out of tricky and heated scenarios quickly and revisit them calmly when emotions are lower.

Come alongside each child

If we could take a moment with each child to listen to their hurts, we would be better able to lead them through the big frustrations between them. This is often better done in privacy without the other child listening but it can be done on the spot too, conveying that we know there are hurt feelings all-round. When my sister was poking me I would have longed for someone to understand my frustration too, that I reacted because I was annoyed, and that my sister had to accept that I didn’t always want to play with her. When we react without recognizing both parties are hurt, we miss the opportunity to come to the child’s side, communicate we are there to help, and address things at a root emotional level.

Don’t force apologies

Forced apologies lead to even more hurt feelings as the obvious lack of genuine caring stings you all over again. What we want is for our kids to feel genuine remorse and this can only come from a place of caring for another person. A cooling- off period is often needed when emotions are high, and when kids come back together to play they will quickly bring their caring to the surface again. When the caring is back, then cue-up the child to make amends.

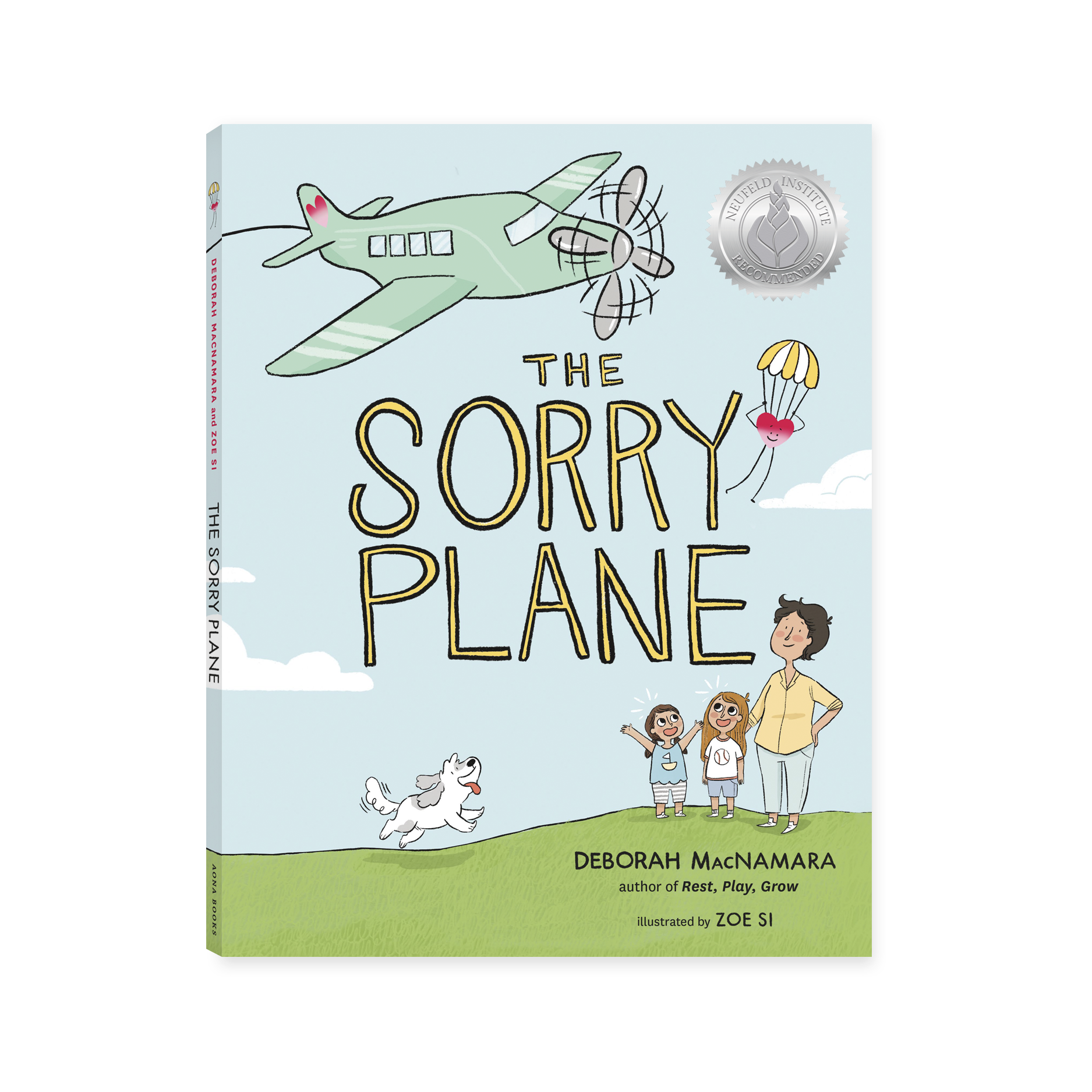

Reading picture books that portray what a real sorry looks like, as it does in The Sorry Plane, is helpful for normalizing frustration as well as conveying the importance of saying you’re sorry from a place of caring.

Get to the root emotion

If children are constantly at each other’s throats, then we might need to step back and take a closer look at what is driving their frustration. Are they enduring a lot of change or hard times at school or home? Are there relationships that are important to them that are not working? It might be time to focus on your relationship with the child rather than dwelling on the relationship between the children to make headway.

Keep them moving

Sometimes we don’t know what to do with our fighting kids but when we get in the lead, things are much more likely to straighten out. Sometimes we need to move them in a different direction: take them outside, get them engaged in a different activity, or spend some one-on-one time with them. When things are going sideways, take the lead and steer the energy into something less hurtful and more productive. Emotions have a way of taking care of themselves if we can keep our kids moving in a healthy direction.

When we see our children unleashing their frustration on each other, it’s better for everyone involved if an adult takes the lead and takes the heat off the child under attack. We can simply communicate that we see they are frustrated, we are there to help, and that siblings aren’t for attacking.

Most kids understand to some degree that their siblings will get frustrated with them. What they have a harder time with is why their parents don’t intervene to help and provide reassurance that the problem isn’t them.

Perhaps if we could accept that kids are immature, that they will fight, and that this is part of our role as parents to help them navigate conflict, then we might find the patience we need when things are coming undone. It is hard to watch them hurt each other but our focus shouldn’t be on making them get along. As mature adults, we just need to make sure we continually express our caring as we deal with a (natural and temporary!) lack of caring in them. •

Dr. Deborah MacNamara is the Director of Kid’s Best Bet counselling center, she is on Faculty at the Neufeld Institute, the author of Rest, Play, Grow: Making Sense of Preschoolers (or anyone who acts like one), which has been translated into 11 languages, and a children’s picture book The Sorry Plane. For more information please see www.macnamara.ca

This article first appeared in the Winter 2020 edition of EcoParent Magazine.